Another paper tiger

By Hilbert Haar

By Hilbert Haar

The Financial Action Task Force has put forty recommendations in place that St. Maarten is supposed to follow. It is all about combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism. The Financial Intelligence Unit or MOT (Meldpunt Ongebruikelijke Transacties) plays a key role in these efforts. The Netherlands Antilles had an MOT that was managed from Curacao and since 10-10-10 St. Maarten has its own reporting center.

If you don’t count the Standard Trust Company and its successor, there seem to be few problems with getting financial and non-financial institutions to abide by the mandatory reporting of unusual transactions. On that level the system works just fine and the MOT is doing what it has to do: registering these transactions, analyzing them and forwarding suspicious transactions for further handling to the prosecutor’s office.

Cash transactions of 10,000 guilders ($5,587) or higher, transactions with checks or traveler’s checks of 100,000 guilders (($55,866) or higher and giro-based transactions of one million guilders ($558,659) or higher all fall under the mandatory reporting guidelines.

The MOT registers thousands upon thousands of unusual transactions every year. So much so, that their total value in 2018 was more than 7.5 times higher than St. Maarten’s Gross Domestic Product.

Unusual does not immediately mean that there is something wrong. The MOT uses defined indicators to determine whether an unusual transaction is normal (or not) based on indicators, before it is categorized as suspicious.

These suspicious transactions are forwarded to the office of the public prosecutor for further handling. In 2018, the prosecutor received 1,345 reports of suspicious transactions. That number immediately makes clear that not all these transactions will become the subject of a criminal investigation. The capacity to do this simply is not there.

The prosecutor’s office therefore has to prioritize – to make choices. Unfortunately, that is where the buck stops.

In its 2016 annual report the prosecutor’s office notes that its investigative capacity is an ongoing problem. There are not enough prosecutors to handle all these reports. Therefore, even the suspicious financial transactions that have made the priority list hardly ever get further than the initial stages of an investigation.

In other words: nothing is done with them. That is hardly the fault of the prosecutor’s office; it has to make do with the resources at its disposal and the scope of those resources is determined by what the government allocates in its budget for investigative capacity.

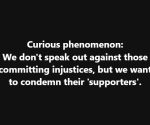

By extension, this is a responsibility of the parliament. How important do members of parliament consider the fight against money laundering and the financing of terrorism to be?

The answer my friends, is blowing in the wind. MPs seem to be more concerned about privacy issues, the origin of people working at the MOT and about the “little man” (who will hardly ever have the cash to conduct a financial transaction worth reporting) than with the real issue.

In that sense, this whole rigmarole about putting institutions and legislation in place to fight money laundering and the financing of terrorism remains just another paper tiger.

###

Related story:

MOT handles billions in unusual financial transactions