Dutch coalition loses majority – sounds familiar?

THE HAGUE – The governing coalition of VVD, CDA, D66 and Christian Union lost its majority in the Dutch parliament last week after the VVD kicked its MP Wybren van Haga first out of the faction and then out of the party. Van Haga continues now as an independent member of parliament. He did not jump ship: he was pushed overboard. The coalition and the opposition now both have 75 seats in the 150-seat parliament.

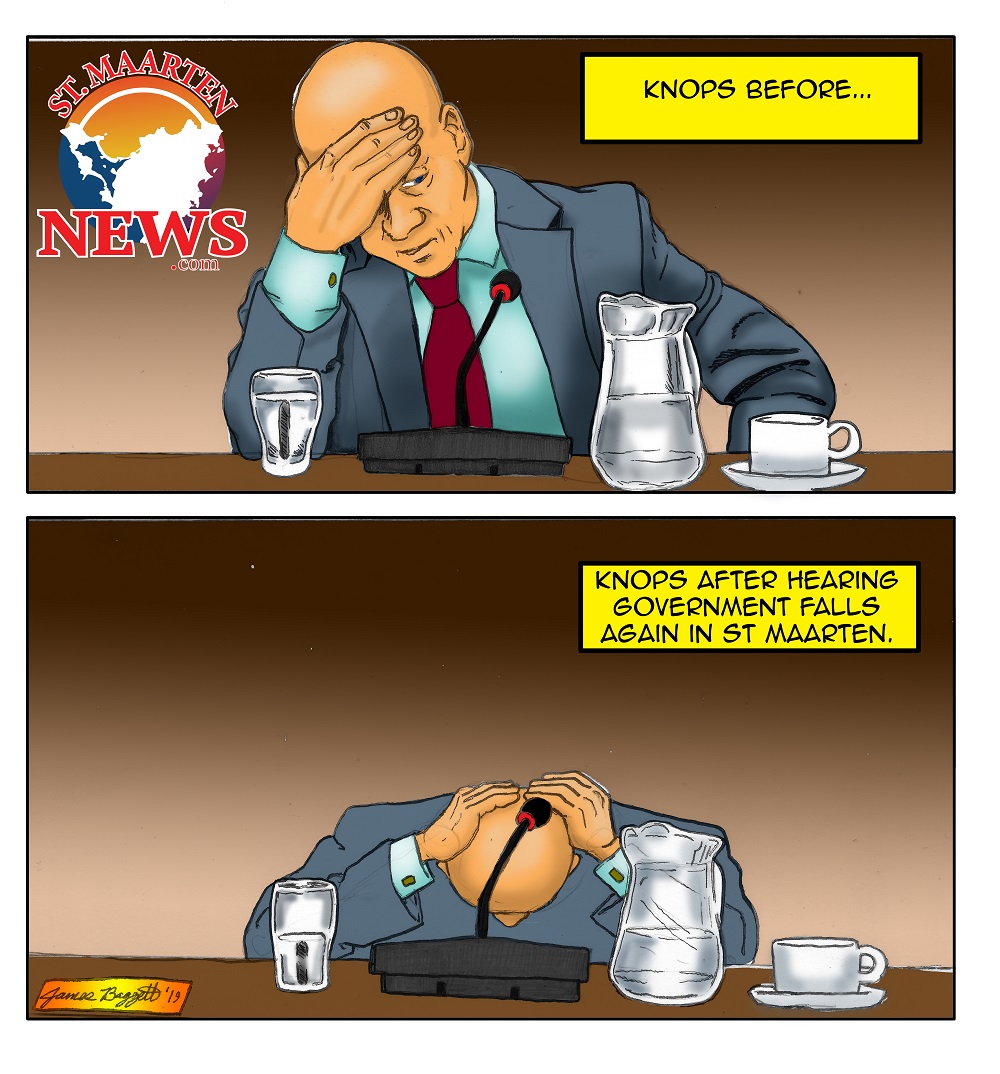

The situation seems similar to the one in St. Maarten when United Democrats faction leader Franklin Meyers declared himself independent. That left the governing coalition with seven seats, while the opposition also held seven. Meyers stood in the middle, not committing himself to the opposition since he had no intention to overthrow the government.

All that changed when UD-MPs Chanel Brownbill and Luc Mercelina defected. The government fell, parliament was dissolved and the country is awaiting elections in January. Not so in the Netherlands.

There are significant differences between politics in St. Maarten and politics in The Hague. The Dutch parliament has 150 seats and consists of thirteen parties and two independent parliamentarians (Van Haga and Van Kooten-Arissen). St. Maarten’s mini-parliament has fifteen seats and just four parties – United Democrats, National Alliance, St. Maarten Christian Party, United St. Maarten party and currently three independents: Brownbill, Mercelina and Meyers.

In the Dutch parliament independents represent 1.3 percent of all seats, in St. Maarten it’s 20 percent.

While Brownbill and Meyers triggered the fall of the government in Philipsburg, the Rutte-government is still in office and there are no signs that anybody wants to go to the polls on the other side of the ocean.

Why is that? Because the Netherlands has a tradition of negotiating while in St. Maarten it is about raw power. When the Rutte-government comes to parliament with a proposal three things can happen. The vote stalls at 75-75 (if all members are present) or the government loses the vote if a coalition-member votes with the opposition. If the issue is important enough, the government could throw in the towel and resign. But the government can also get support from one or more opposition members – it is all a matter of making deals.

The VVD ousted its faction member Wybren van Haga after a series of incidents – from drunk driving to Haga’s involvement with his real estate business after he had promised the party to stay away from it.

Van Haga did not give his seat back to the party and the opinions about this decision are divided. One argument is that seats in parliament are assigned to individuals, not to parties. Another argument is that a lot of parliamentarians get their seats by surfing on the coattails of their party leader and that therefore the party owns the seat. The Dutch Constitution says otherwise.

Van Haga is a typical example of parliamentarians that fall into the coattails-category. As the number 41 on the VVD-list for the 2017 parliamentary elections he did not stand a chance to make it into parliament. His elections result: a meager 2,159 votes while the threshold to win one seat was 70,106. But because the VVD went into government with six ministers and three state secretaries, Van Haga just slipped into the number 32 seat.

So while the Dutch coalition has lost its majority it has not lost its ability to govern. If Brownbill and Mercelina had not made their opportunistic move in September, St. Maarten would not have the need for elections either. Parliament could have simply taken issues brought to the floor on a case by case basis and vote for or against.

On the French side of the island governments never seem to fall. President Daniel Gibbs once told the Today newspaper that this is how things work in Marigot: sometimes the opposition votes in favor, sometimes it votes against and sometimes coalition members vote with the opposition. Everybody lives with the result of the vote.

There is a lesson to be learned from these examples but knowing St. Maarten’s political history it will be a rainy day in hell before politicians come to their senses and start acting in the interest of the country and its citizens.