PHILIPSBURG -– On May 31, Ronald Dongor passed away at the age of 72 in his residence in Amersfoort in The Netherlands. His death did not attract any attention, until the Dutch quality newspaper Trouw recently published a tribute to the man who wanted to become a priest but ended up instead as a colonel in the Royal Dutch Marechaussee, the military police. After his retirement, at the age of 55, Dongor spent two years in St. Maarten – between 2008 and 2010 – as a coach for the local police force.

The chief of police at the time, Franklyn Richards, and Chief Prosecutor Hans Mos were both at hand to say goodbye to Dongor, two days before he left the island on May 14, 2010. On November 19, 2009, Dongor was a speaker at a meeting of the local Rotary chapter where he explained the process to upgrade the police force to meet the standards of the European Union.

Ronald Dongor was not just anybody. He was born in Moengo, a town in the Marowijne district in Suriname with a population of just under 11,000, in a family with eleven brothers and sisters. His father started out as a policeman and later went to work for the bauxite mining company Suralco.

Dongor was religious and claimed to have two connections with God. One of them was direct and the other connection flowed through other people.

The Trouw-article describes Dongor as an intelligent boy who completed the Atheneum in Paramaribo. His desire to become a priest did not materialize due to that other desire: to become, just like his father, a policeman. He received a grant to study at the police academy in the Netherlands, but that grant disappeared under political pressure.

Undeterred, Dongor took a job at an accountancy firm where he realized soon enough that counting numbers was not his thing. He reported to the army as a conscript and then received an invitation to do an officers training in The Netherlands. After six months he returned to Suriname as the country’s first ensign-bearer. Only a few months later he was selected for training at the Royal Military Academy in Breda.

In 1979 – a year after he married his wife Joan – he returned to Suriname for a job as the acting commander of the military police. Shortly after his arrival, on February 25, 1980, Desi Bouterse committed a coup d’etat.

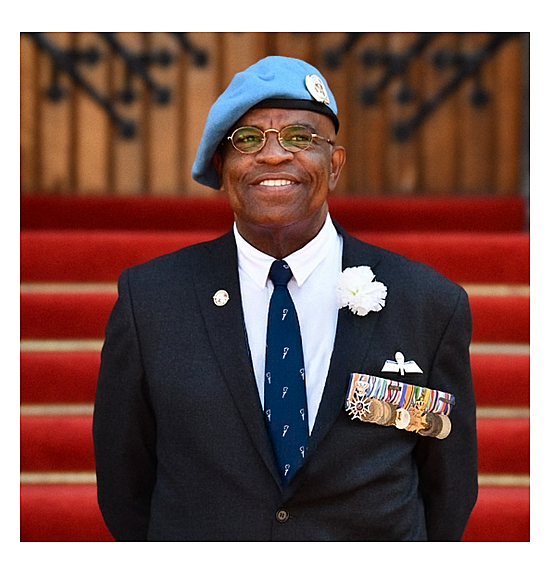

The new sheriffs in town ill-treated Dongor and kept him imprisoned for months. After his release, he fled with his wife to The Netherlands; a year later he was sworn in as a member of the Marechaussee. He made a career there and reached the rank of colonel.

“That was not easy,” Trouw wrote. “As a black man in a white and strongly hierarchic environment he had to put in extra efforts to prove himself.” That’s what he did and, according to Trouw, his disarming friendliness and his laughter made him a popular manager.

Dongor went on a United Nations mission to the now former Yugoslavia where he was taken hostage for several days by Serbs. Trouw: “He saw the dehumanizing consequences of genocide. He saw bombs explode and colleagues die.”

These were obviously bad experiences but they did not break Dongor. A year after the war was over, he returned to Sarajevo, tasked with controlling the local police force.

Back in the Netherlands he took part in the security measures surrounding the marriage of Willem-Alexander and Maxima in 2002. The crown on his work was his responsibility for the protection of Pope John Paul II during a peace-visit to Bosnia-Herzegovina in 2003. Afterwards, the pope personally thanked Dongor for his efforts.

In 2007, at the age of 55, Dongor retired and he was decorated as Knight in the Order of Orange-Nassau with swords.

Surprisingly, Dongor was not done yet. He did not start sipping margueritas under a palm tree. Instead, he traveled with his wife Joan to St. Maarten where, according to the Trouw-article, he worked as the chief of police. Later he even returned to Suriname where he provided training to the local police force and the national security services. He also designed a bachelors-training for police science. “Suriname is my fatherland, the Netherlands is my motherland,” he used to say.

Back in the Netherlands, as a sixty-year old, he became active as a choir-singer and a lecturer in the Roman Catholic Church in Hoogland. He also played keyboards and organ and spent time with his two grandchildren, Nova and Joah.

Unfortunately, after such a rich and decorated career, there was no happy ending. In 2014 Dongor was diagnosed with Kahler’s disease, a form of bone cancer that usually hits people over the age of sixty. It ultimately landed him in a wheelchair. He spent the last months of his life in a hospital where visitors at times had to queue up when they came to see him.

Ronald Dongor died on May 31, 2025.

###

ADVERTISEMENT