A flaw in the corporate governance code

PHILIPSBURG – On February 26, 2010, the Executive Council of Island territory St. Maarten introduced the first Corporate Governance Council. William Marlin, at the time leader of the island government, addressed the council members – Louis Duzanson, Minerva Vlaun-Monte, Francis Carty, Maria van der Sluis-Plantz and Agnes Gumbs – and told them that they had a huge task ahead of them. “You are the first to be appointed to the council and what it will become depends mainly on you.”

Little did those council-members know how true those words would turn out to be. Government-owned companies like the harbor, the airport and Gebe were supposed to fund the corporate governance council, but that alone appeared to be a problem. In the initial stages, the council did not get any cooperation.

The next year, on December 19, 2011 – the island territory had in the meantime become ‘country’ St. Maarten – parliamentarian Leroy de Weever said in parliament that the council was “prohibitively expensive” while it remained unclear what this body would do for the government.

“I don’t need any corporate governance council to tell my ministers to pull up their socks. This is squandering taxpayers’ money.”

De Weever said that he will propose to disband the council and that he does not need anybody to tell him what to do. “This is a way to frustrate the government.”

Remarkable, because De Weever was the chairman of the central committee that proposed to establish the corporate governance code and the council.

Throughout the years it became abundantly clear that the same politicians who had given the green light for the establishment of the Corporate Governance Council, were quick to ignore the rules when it fit their objectives.

The appointment of Regina Labega as director of the airport is a typical example. Labega was appointed per July 1, 2011, even though there were already then suspicions about embezzlement in her previous function as director of the Tourist Bureau. The airport-position is a so-called position of confidence that requires a certificate of no objection, to be issued by the minister of general affairs after screening by the national security service VDSM.

The appointment did not go through that process, nor was there an advice from the Corporate Governance Council. Had the council been asked, it would have had no other choice then to issue a negative advice.

Labega was removed from her function years later, after she failed the belated VDSM-screening, whereupon Prime Minister Marcel Gumbs refused to issue her a declaration of no objection.

While this example shows how government-owned companies remain the favorite plaything of politicians, the code itself also contains a serious flaw. Because politicians are happy with that flaw, nobody ever talks about it. But it has in the past already resulted in the resignation of supervisory board members who do not want to be responsible for actions of management they are unable to control.

The flaw is in article 22 of the Corporate Governance Code. It reads: “The supervisory board shall reach explicit agreements with the management as to which information the supervisory directors will receive, to what degree of detailing and how frequent.”

The same article says that management will have to provide accurate, complete and timely information to the supervisory board. Furthermore: “The supervisory director who does not receive the information necessary for his proper judgment, will explicitly request for same, from management, which must be submitted within reasonable bounds.”

What is the flaw in all this? First of all, the supervisory board must come to an agreement with management about the information it will receive.

The argument against this rule is obviously that supervisory boards must be able to get all information about the way a state-owned company is run. But the code leaves the flow of information open for negotiation. It tilts the balance of power between management and a supervisory board in favor of management.

Secondly, all supervisory board members can do when they do not receive the information they need is this: ask for it again. There is no sanction if management does not honor such a request.

In the meantime, supervisory directors remain responsible for whatever a state-owned company does. If they have some, but not all information, they find themselves on a slippery slope. They’ll have to accept responsibility blindfolded and with at least one hand tied behind their back.

Look at what went on at the harbor group of companies for years: director Mingo signed forged invoices for amounts just below the 50,000 guilders so that he did not need approval from the supervisory board. Had those invoices gone to the board, somebody would have woken up to Mingo’s shenanigans and put a stop to this multi-million dollar theft.

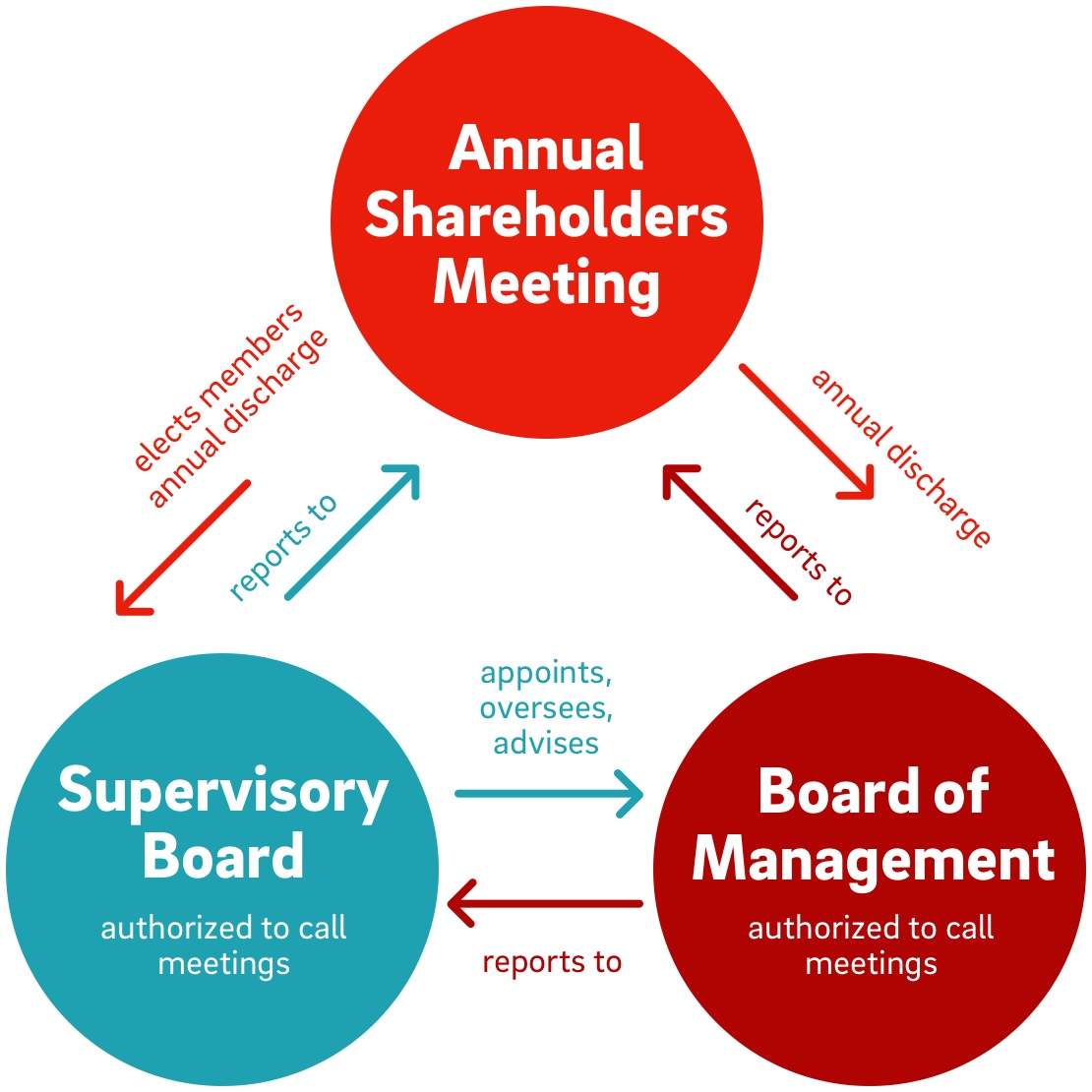

Supervisory boards should not interfere with the day to day management of a state-owned company, though under political pressure this happens all too frequently at different companies. The corporate governance code mentions as the first task for these boards: “See to it that the general course of affairs takes place in a proper manner.”

The code specifies a list of seventeen other topics those boards have to pay attention to, but the main task is to control management. That can only be done if management provides the board with unrestricted access to all information relevant to the execution of this task. The purpose is not to frustrate management, but to make sure that the company does what it is supposed to do, based on applicable law.

In this context it is rather surprising that the harbor managed to get the Walter Plantz Square project off the ground. Sure, it adds some flavor to the Philipsburg experience in an area that was otherwise more or less dead, but the project does not add anything to the harbor’s bottom line.

Windward Roads executed this project at a reported cost of $2 million. It caught the attention of researchers of PriceWaterhouseCoopers; the company’s 2014 integrity report found that “one government-owned company” had outsourced a $2 million construction contract “to a family member of one of the company’s supervisory board of directors.”