Cursed Circles

By Hilbert Haar

Years ago, as I was sitting on my balcony in the Cretan sun, the mailman stopped by and asked if I had a banknote of twenty Deutsch Marks. It was quite an odd request as Greece was still using the Drachme as legal tender at the time. So I asked him why on earth he needed German currency. What was he going to do with it?

It soon became clear to me that my mailman had been caught in a trap – call it a pyramid scheme, a Ponzi scheme or a Blessings Circle, they are all birds of a feather. I told the mailman that he could also give the money to me because the result would be the same: he would never see it again. That way I saved one man from losing his money in a fraudulent scheme.

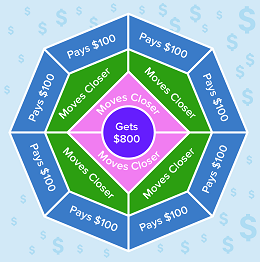

These days it is all about the so-called Blessings Circle on our islands, a clever moniker in a region where religion plays a big part in the lives of many people. The Central bank issued a warning about this scam and listed five characteristics that are worth repeating here: 1. Emphasis on recruiting, 2. Promise of high return in short term, 3. Complex commission structure, 4. No genuine product or service is offered and 5. Easy money.

This pyramid scheme plays on the insecurity many people experience as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. But the attraction of these schemes comes down to only one characteristic: easy money.

Why is it that so many people are unable to understand this: when it is too good to be true it usually is? There is no such thing as a free lunch, to use a well-worn cliché, and easy money does not exist. And yet, Ponzi-schemes already existed long before its namesake sprang into action in the 1920s of last century.

The German actress and con-artist Adele Spitzeder opened a bank in 1869 and swindled 32,000 investors out of the equivalent of more than $470 million by promising high returns on investments and by financing these promises with the money of new investors. The collapse of her bank in 1872 was followed by a wave of suicides.

The American fraudster Sarah Emily Howe was the architect of the Ladies’ Deposit Company in Boston, a savings bank that accepted only deposits from unmarried women. Howe promised high interest rates but she did what Spitzeder did in Germany: robbing Peter to pay Paul. She never advertised but nevertheless managed to convince 1,200 unmarried women to deposit $500,000 into het fraudulent scheme. It collapsed in October 1880 and Howe went to jail for fraud.

The Italian swindler and con-artist Charles Ponzi took pyramid schemes to the next level forty years later. In the 1920s he promised investors 50 percent profit within 45 days and 100 percent profit within 90 days. Of course, he paid his early investors with money he received from new investors. Maybe it was not original but Americans fell for the scam in droves. The loss for his investors was around $20 million when the scheme collapsed after a year.

Ponzi may have been inspired by William Miller, a bookkeeper from Brooklyn who raked in $1 million in 1899 with a similar deception. But somehow Ponzi’s name stuck and pyramid schemes are now generally referred to as Ponzi-schemes.

Because there are no laws against stupidity or ignorance, it is difficult to protect potential victims against the operators of these schemes. I figure that the people who are reading this column don’t even need that protection – because they already know that easy money does not exist.

But the fraudsters among us – and there is an endless supply of them –know that if you manage to approach enough people there will always be a tiny percentage that will fall into their trap. Saying to those victims “I told you so” does not make a lot of sense because with them, greed and ignorance will always win from common sense Sad but true.

###

Related news:

Central Bank issues warning about Pyramid Schemes

Youtube video about Blessing Circles

Illegal pyramid schemes are on the rise during the pandemic